The Eviction of the Temecula Indians

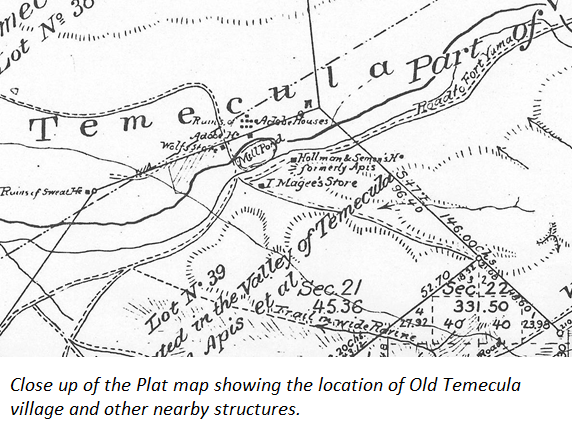

The Eviction of the Temecula Indians is one of the most significant events in the history of the Pechanga people. The Eviction, which took place between September 20 and September 23, 1875, stripped the Indians, known at that time as the Temecula Indians, of their homes, their livelihoods, and many of their possessions. The village was located along Temecula Creek near what is now the Redhawk housing development (Highway 79 South).

The Indians at “Old Temecula Village”

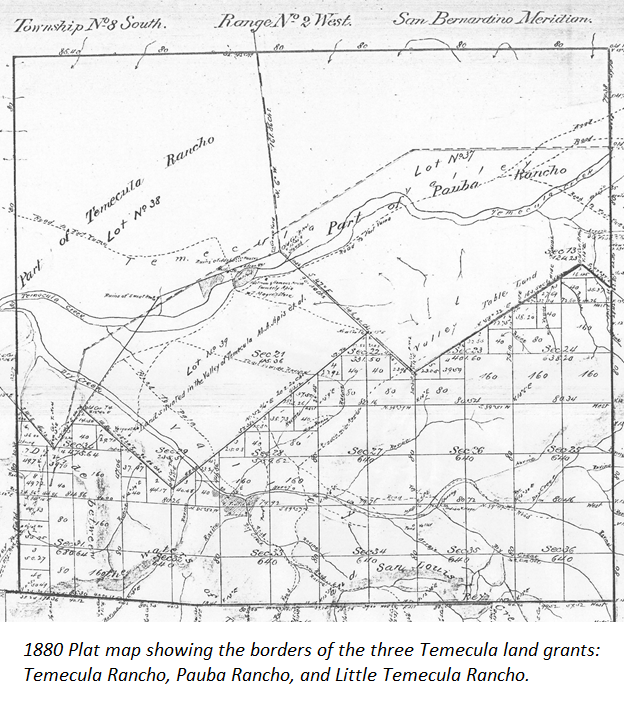

In the 1840s, three land grants were created in the Temecula Valley: the Temecula Rancho, the Little Temecula Rancho, and the Pauba Rancho. Temecula Village was located within the borders of Little Temecula Rancho. Little Temecula was originally granted to Pablo Apis by San Luis Rey Mission Father José María Zalvadea and Administrator José Joaquin Ortega.

Apis was born at Guajome village near Oceanside. He began living at Mission San Luis Rey when he was about 6 years old. While at the Mission, he learned to read and write Spanish. Later, the Mission fathers appointed Apis to the position of alcalde. In 1843, he moved to the 2,200-acre Little Temecula Rancho, which was officially granted to him in 1845 by Governor Pio Pico. It was unusual for the Mexican government to grant land to Native people. Pablo Apis allowed other Luiseño people to live and work on his land, and in time, there was a thriving village at the Little Temecula Rancho.

Apis was born at Guajome village near Oceanside. He began living at Mission San Luis Rey when he was about 6 years old. While at the Mission, he learned to read and write Spanish. Later, the Mission fathers appointed Apis to the position of alcalde. In 1843, he moved to the 2,200-acre Little Temecula Rancho, which was officially granted to him in 1845 by Governor Pio Pico. It was unusual for the Mexican government to grant land to Native people. Pablo Apis allowed other Luiseño people to live and work on his land, and in time, there was a thriving village at the Little Temecula Rancho.

Though part of the Little Temecula Rancho was owned by members of the Apis family for several generations, it was gradually sold away in parcels. It wasn’t long before this Luiseño village was threatened by newcomers, despite a stipulation in the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (the agreement that ended the Mexican-American War), which stated that Indians in the former Mexican territory were allowed to stay in their existing villages as U.S. citizens. In 1859, two men who purchased part of Little Temecula, David Holman and Charles Seaman, wanted clarification about where their property ended and the Indian village began. Juan Machado, the town magistrate, drew new boundary lines around the village on Little Temecula that separated the village from nearby farm fields.

Though part of the Little Temecula Rancho was owned by members of the Apis family for several generations, it was gradually sold away in parcels. It wasn’t long before this Luiseño village was threatened by newcomers, despite a stipulation in the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (the agreement that ended the Mexican-American War), which stated that Indians in the former Mexican territory were allowed to stay in their existing villages as U.S. citizens. In 1859, two men who purchased part of Little Temecula, David Holman and Charles Seaman, wanted clarification about where their property ended and the Indian village began. Juan Machado, the town magistrate, drew new boundary lines around the village on Little Temecula that separated the village from nearby farm fields.

The Temecula Indians were unhappy because the new borders gave the land they had been farming for decades to Holman and Seaman. With the help of a local Indian Agent, the Temecula Indians took Holman and Seaman to court in 1859. Though Commissioner George Pendleton determined that Holman & Seaman could keep the farm fields outlined by the new boundaries, he stated that the Temecula people could keep their village and their access to water. Pendleton also gave them a different parcel of land near their village for farming purposes. Although their victory was not a complete one, the Temecula people now had legal rights to the land they lived on.

Events Leading to the Eviction

As the years passed, the Apis family sold more pieces of Little Temecula Rancho until only the family home and three surrounding acres remained in family hands. In 1873, Domingo Pujol, Francisco Sanjurjo and Juan Murrieta purchased the majority of the Little Temecula, Temecula, and Pauba ranchos. John Magee and Louis Wolf also owned parts of the Little Temecula Rancho.

The new landowners moved thousands of sheep onto the ranchos. The Temecula Indians constantly had to drive the sheep out of their gardens and fields. They did this for years without complaint until some sheep destroyed a man’s wheat field about 1875. He complained to the ranch foreman, and they argued. The foreman reported the incident to the owners. Soon after, the San Diego County Sheriff served a Decree of Ejection to the Temecula Indians.

A first-hand account provided by Josefa Yuhac, a Luiseño woman who lived through the Eviction, relates the particular incident that may have led to the ranchers’ decision to seek an eviction order:

“Pá' pó' vorigéerom ponéemi pom'áshmi qamí''ik, pá' pomóm şuláaqanik, táapik ponéy 'atáaxum pom-míyxi. Pí' pomóm xwáyyaantum yaqáanik, pomóomi şuwóo'quş. 'oyóok kíivik pom'áshmi ponéemi.

Pí' 'áawquş pó' 'axá'po, pó'…Filipíito Hóowaq. Pó' wéhmali po'áachum múyyukum míyxuk…pó' pomíxnga pó' şuku múuluk poşáax híycha wuníyk. Po'éex múuluk. Pí' 'aşúnnga pomóomi şuláqqik ponéemi po'áshmi, pó' háx híycha vorigéero. Pá' pomóm ponéy táapik. Pomíx. Pó' muyáqqik ‘oyóok ya’ásh Hóowaq pó’ Filipíito puyáamangay 'íyxuk. Puyáamangay póy nginángninik, pá' şuku kuná' 'íyxmaqanik wukó’ya pó’ 'atáax. Michá' 'axánya, mán şuku woltú'ya michá' 'axánninik póoxa poşúnngay…Pá' pó' 'áshkat chelí'chelik Filipíito. Pá' kuná' póy po'óo'olmi kuná' míyquş. Póoxa pomá'maxi wám', néqpivichuquş, pó' vorigéero, pí' pó' póy láachaquş, 'íyqal. Qáy póy néqpax michá' 'axánninik. Mán húukax, yáawaquş. Po’áshmi ponéemi wám' 'ínnax 'ivíyk pó' chúuchumi. Pó' póoxa kuná' póy láachaquş. Híyquş. 'óo'olmiquş. Michá' 'íyquş, pó' vorigéero. Pá' 'áy'ngim po'áshmi.

Pó' puyáamangay 'ókkik 'atáaxum ponéy pom-míyxi 'íyxuk, pí' şuku wóltuquş. 'ayálkaquş michá’ 'íyquş. Şuwóo'quş. “Néy chá'qwiktum pitóo," yaqúş. "Mán, tée michá' 'axánniktum wóş kuná’." Poşúun powóoyax. Pá' pó' híknga teméenga 'ichá'po ku pá' pó' wám' tóotupax ponóo'u póyk pó' háx Murrieta híycha, pó' 'axánninik póy 'íindiyo wuná' poloví''iqala, po'áshluqala, pongáariqala híshmi múyyukmi voregíitomi híshmi…chúuchum. Pá' pó' woltú'ya háx Murrieta.”

“Then the sheep ranchers let their livestock graze unchecked, and once they came in, they (the sheep) destroyed Luiseño property. And the ones they called white people, they (the Luiseño) were afraid of them. They (the Luiseño) would quietly drive out their herds (the herds of the foreign sheep ranchers).

And there was this what's his name…Felipito Hóowaq. He had quite a few animals…On his property the wheat used to sprout up in abundance. His land was fertile (and/or well irrigated). And he (a foreigner) let his livestock in (onto Mr. Hóowaq's land), that sheep rancher, or whoever or whatever he was. And they (the sheep) finished it (the wheat) off. It was his (Mr. Hóowaq's) property. That man Hóowaq, Felipito, also kept driving them (the foreign livestock) quietly back out (off his land). After he (the sheep rancher) had repeatedly offended him (Mr. Hóowaq), that person (the sheep rancher) finally came (over to Mr. Hóowaq). Something happened, and so he (the rancher) got mad at him (Mr. Hóowaq) for some reason…So that (Luiseño) rancher, Felipito, pushed them out. So then he (the foreign sheep rancher) insulted him (Mr. Hóowaq). The sheep rancher was just looking for a fight, and he (Mr. Hóowaq) was just arguing with him (the foreigner). He (Mr. Hóowaq) didn't physically fight him (the foreigner) in any way, nor did he challenge him, no such thing. He (Mr. Hóowaq) had just removed his (the rancher's) animals, over this way, with his dogs. He was just arguing with him. He was saying things. He (the foreign rancher) was insulting him. Something was wrong with that sheep rancher. Then he (Mr. Hóowaq) took away his (the rancher's) animals (off of Mr. Hóowaq's land).

He (Mr. Hóowaq) also constantly sought to preserve Luiseño property, and so he got angry. He sensed that something was wrong. He was afraid. He was saying, “Now they are going to get me,” or “Who knows what they are going to do.” That’s what he was thinking. Then after I don’t know how many days, that what’s-his-name (the sheep rancher) reported to his leader, that Murrieta guy, whoever he was, about what that Indian had done, that he (the Luiseño man) was increasing his own herd, about how he (the Luiseño man) had tied up all those sheep, those animals…the dogs. And then that Murrieta guy got angry.”

Some of the local ranchers were able to obtain a Writ of Ejectment from the San Francisco courts because the Indians could not prove they owned the land, despite the 1859 court ruling. The writ was served on September 9th, and the people were given until September 20th to move off the rancho. The writ contained the names of 52 heads of household, representing over 200 people. The new owners told the Temecula Indians they could remain in their homes if they signed leases. The Indians refused to do this, sometimes out of principle, and sometimes because they could not afford the rent.

The Eviction

On September 20, 1875, under orders from the District Court of San Francisco, Sheriff Nicholas Hunsaker of San Diego and approximately twenty armed men evicted the Temecula Indians from their traditional village. The eviction took place over three days.

The posse led by Sheriff Hunsaker, who was paid $300 for the job, included the owners of the ranch, as well as local landowners Louis Wolf and José Gonzales. The men drove wagons to the Indians’ homes and loaded their belongings in them. The Indians did not fight back because the posse members told them that anyone who resisted would be shot.

The Temecula people protested by sitting down and refusing to move any of their belongings. Once the wagons were full, the people were forced to leave the village, following behind the wagons. They had to abandon their crops and most of their livestock. The posse shouted insults and threw stones to get them to move along. Once they were beyond the borders of the rancho, a hike of about three miles, the posse members emptied the wagons onto the ground. They were not careful, and they broke many of the people’s belongings, including pots that contained food. The evictees salvaged what they could and looked for a new place to go.

John Magee, one of Temecula’s early American settlers, invited the Temecula people to stay on his land until they figured out what to do. He owned a store near the place the Indians and their belongings had been dumped, and his wife, Custoria Nesecat, was a Temecula (Pechanga) Indian woman. Those who chose to stay on Magee’s land settled near the foothills where they had access to water. Others chose to live in nearby Pechanga Canyon.

John Magee, one of Temecula’s early American settlers, invited the Temecula people to stay on his land until they figured out what to do. He owned a store near the place the Indians and their belongings had been dumped, and his wife, Custoria Nesecat, was a Temecula (Pechanga) Indian woman. Those who chose to stay on Magee’s land settled near the foothills where they had access to water. Others chose to live in nearby Pechanga Canyon.

After the Eviction

Life for the evictees was very difficult at first. They worked hard to make new lives, but they still struggled to get by for several years. Not only did the Temecula people have to rebuild their entire lives, they also suffered continued animosity from the ranchers and landowners who had forced them from their homes. For example, many Indians lost their livestock, which naturally wandered back to the old village where they had once lived. Juan Murrieta corralled the animals and refused to return them to the evictees unless they compensated him for the animals’ recapture. Murrieta sold the livestock of anyone who could not reimburse him.

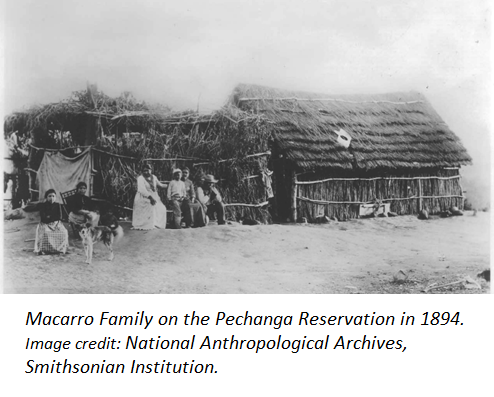

Helen Hunt Jackson, the future author of Ramona, visited the Temecula people shortly after the eviction and interviewed people about what had happened. Jackson was working for the Bureau of Indians affairs at the time, and she was quick to send the story of the eviction and the evictees’ appalling living conditions to the U.S. Government. Her reports helped convince Congress to set aside land for the Pechanga Reservation, which was established by Executive Order on June 27, 1882 by President Chester A. Arthur. When Jackson returned to Pechanga in 1883, she was pleased to see that the Pechanga people were thriving despite their recent mistreatment. She reported that the Pechanga people had built houses and dug wells, and they were farming the land more successfully than their non-Indian neighbors were. The Pechaángayam refused to be defeated despite the hardships they had endured.

Our canyon and the Pech

Our canyon and the Pech