Timeline

Important Events in the Temecula Valley

Time Immemorial to 10,000 Years Ago: The Creation of the World at ‘Éxva Teméeku.

The original peoples of the Valley, now identified as Luiseño Indians, inhabited the larger Temecula area for thousands of years. Evidence of their villages survives throughout the valley in the form of bedrock mortars, stone tools, pottery, and rock art. The traditional Tribal boundaries include all of western Riverside County and northern San Diego County.

1769: Father Junípero Serra establishes the Mission San Diego De la Alcalá, the first mission in Alta California

1776: Mission San Juan Capistrano is established and many Temecula people are taken to this mission

1797: Spanish Missionaries Arrive in the Temecula Valley

Father Juan Norberto de Santiago records passing through the Temecula Valley during an exploratory journey to identify possible sites for future missions

1798: Mission San Luis Rey de Francia established in Luiseño Ancestral Territory

1816: Mission San Antonio de Pala, built as a local asistencia under the jurisdiction of Mission San Luis Rey, served the inland Luiseño populations

1821: Mexico declares independence from Spain, and California becomes Mexican territory

1833-1834: The Mexican government secularizes the missions

1846-1848: Mexican-American War

California is part of the huge territory granted to the U.S. by the terms of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which was signed in February of 1848.

1847: Temecula Massacre

1848: Gold is discovered in Northern California near Sutter’s Mill

While there was not much mining occurring in the Temecula Valley during the Gold Rush era, people in the Temecula Valley were affected by the demand for raw materials, particularly food. Several prospectors travelled through the valley following the southern Yuma route on their way to the gold fields. The number of ranches and farms in the valley grew enormously during the 1840s through the 1880s. The Native people in Temecula Valley, known at this time as Temecula Indians, were pushed toward the edges of their ancestral lands. They lost access to reliable sources of water, traditional food sources, and religious sites as a result.

1850: California Becomes A State

One of the unfortunate effects of statehood on California’s Native people was the passing of “An Act for the Governance and Protection of Indians” on April 22, 1850. This Act and its 1860 Amendments permitted American citizens “to have the care, custody, control and earnings of such [Indian] minor until he or she obtain the age of majority." The later amendments allowed adult Indians to be “indentured” (enslaved) in the same way. Though the Act of 1850 was intended to keep homeless Indians off the streets, unscrupulous people used it as way to enslave Indians and keep them in a vicious cycle of indenture. Wages were often paid in the form of alcohol and rancho owners would post bail and force the people to work off the debt.

1852: Treaty of Temecula

The Treaty of Temecula was one of 18 unratified treaties signed by representatives of nearly 200 California tribes throughout the state. The U.S. Senate refused to ratify any of the treaties and the original documents were considered “lost” until 1905.

1858: First Butterfield Overland Stagecoach arrived in Temecula

1859: First Post Office opened in Temecula Valley

Having a post office made Temecula’s cityhood official.

1875: Eviction of Temecula Indians

A group of Temecula Valley ranchers petitioned the San Francisco District Court for permission to evict the Temecula Indians from their villages. The judge agreed to the eviction, ignoring the fact that the Indians had lived there for generations under the terms of a Mexican land grant. The eviction took place between September 20 and 23, 1875. José Gonzales, Juan Murrieta, Louis Wolf, and several other local landowners formed an armed posse, assisted by Sherriff Hunsaker of San Diego. The posse members loaded the contents of each home into wagons and dumped everything about three miles to the south, forcing the Indians to follow the wagons on foot while insults and rocks were hurled at them.

1882: First train stops in Temecula on January 23, 1882

1882: Pechanga Reservation established by Executive order on June 27, 1882

President Chester A. Arthur signed the Executive Order that established the Pechanga Indian Reservation. The name comes from the place where the Temecula Indians settled after they were evicted from the Ranchos. Author Helen Hunt Jackson was instrumental in securing reservation land for the Pechanga people. She visited Temecula shortly after the Temecula Eviction. At that time, Jackson was a U.S. government agent investigating the living conditions of Southern California Indians. She included several first-hand accounts of the Eviction in her report, which helped sway government opinion in favor of the Indians.

1891: The Allotment of family-owned land plots begins on Pechanga Reservation

1905: Vail Ranch founded by Walter L. Vail

For nearly 60 years, Vail Ranch was a significant economic force in the Temecula Valley, and many of its employees were Indians from Pechanga, Pala, Rincon, Soboba, and Cahuilla Reservations.

1907: Kelsey Tract added to Pechanga Reservation to create additional farmland for the people

1914: The First National Bank of Temecula opens

Located on Front Street in Old Town Temecula, the First National Bank building is now a restaurant.

1914-1918: World War I

Many young men from the Temecula Valley were soldiers in WWI. Their number included a significant percentage of Native Californians who were just as patriotic as any European-American, despite the fact that few of them were recognized as American citizens at this time. After the war, most Native soldiers and sailors were granted citizenship in recognition of their service.

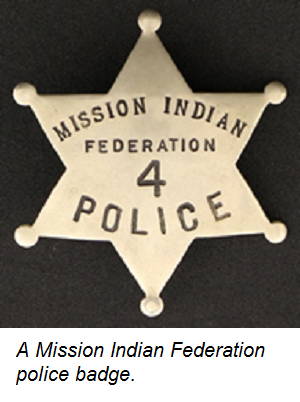

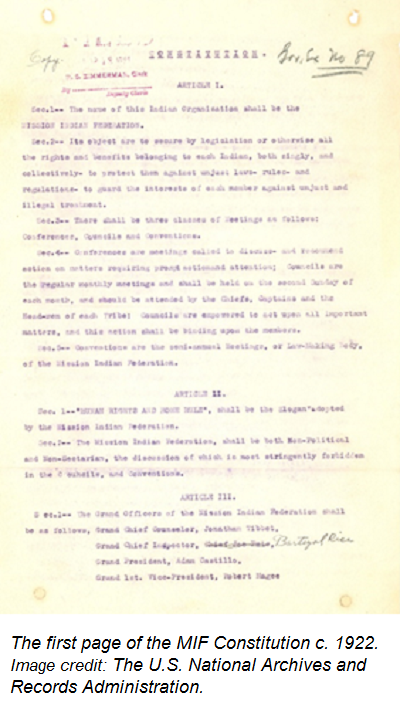

1919: The Mission Indian Federation was founded

The Mission Indian Federation (MIF) was the first Native American Civil Rights groups founded and operated by Southern California Indians. Their primary goals were freedom from the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) and full citizenship rights for all Native Americans.

1924: Indian Citizenship Act is passed

The passage of the Indian Citizenship Act on June 2, 1924 granted all Native Americans full U.S. citizenship. This law did not affect all Indians equally, however. In California, Indians who lived on reservations were still considered “wards of the state,” and were subject to BIA control for several more decades.

1939-1945: World War II

As in World War I, many men from the Temecula Valley fought in WWII. The most decorated WWII veteran, Audie Murphy, owned a horse ranch in Menifee from 1957 to 1963.

1953-1964: Indian Termination Policies enacted

U.S. Indian Termination policies effectively forced the assimilation of over 100 formerly recognized Native American tribes by closing their reservations and cutting them off from the services they had received through the federal government. While none of the Tribes in the Temecula Valley were slated for Termination, they were affected by some of the laws made during the Termination Era.

- Public Law 280, 1953: Tribes who maintained federal recognition were still affected by Termination policies such as Public Law 280, which greatly reduced the control of the BIA on Indian reservations but made reservation Indians subject to state laws.

1964: Vail Ranch is sold

Developers purchased the ranch property and built the Rancho California community. This development encouraged people who worked in neighboring counties to move to Temecula.

1970s: Pechanga Senior Center and first Tribal Government Center built

1978: Indian Child and Welfare Act (ICWA) and the American Indian Religious Freedom Act passed

1988: Indian Gaming Regulatory Act passed

Indian Gaming in the Temecula Valley has not only helped to improve the lives of Native people, but also the communities around the reservations. The casinos at Pechanga, Pala, Pauma, Soboba, and Lake Elsinore employ thousands of local people and generate millions of dollars of tax revenue every year. The tribes also donate money to local charities and public works projects.

1990: Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) passed

1995: First Pechanga Casino is built

1998: Proposition 5 passed

Prop 5, formally known as the Tribal Government Gaming and Economic Self-Sufficiency Act, allowed California tribes to make compacts with the state if they wished to expand their gaming operations to include casino-style gaming. Prop 5 was quickly replaced by Prop 1A in 2000 because it amended California’s constitution to make casino-style gaming legal.

2002: Pechanga Chámmakilawish School opened

2003: Great Oak Ranch property is purchased by Pechanga and put into trust

2007: Pechanga Cultural Center opened

2012: Pechanga purchases Pu’éska Mountain

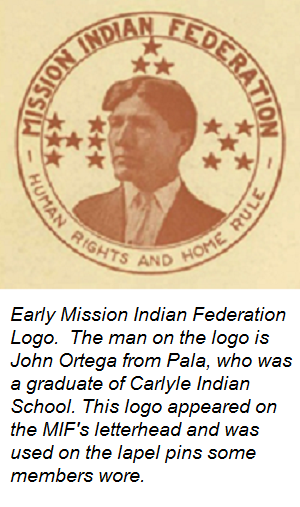

The Federation's motto, "Human Rights and Home Rule" was the core of their fight for civil rights and Indian autonomy on the reservations. At the time of the formation of the organization, Native Americans were not citizens of the United States. MIF members argued that it was unjust for native-born Americans to be denied U.S. citizenship rights when immigrants could become citizens after just a few years in this country. They believed that Indians would never be treated as full citizens as long as the BIA was allowed to oppress and exploit Native people. Specifically, the MIF called for the dissolution of the BIA and its associated subsidiaries, the right for tribes to own their reservation lands, and the right to self-determination enjoyed by all American citizens.

The Federation's motto, "Human Rights and Home Rule" was the core of their fight for civil rights and Indian autonomy on the reservations. At the time of the formation of the organization, Native Americans were not citizens of the United States. MIF members argued that it was unjust for native-born Americans to be denied U.S. citizenship rights when immigrants could become citizens after just a few years in this country. They believed that Indians would never be treated as full citizens as long as the BIA was allowed to oppress and exploit Native people. Specifically, the MIF called for the dissolution of the BIA and its associated subsidiaries, the right for tribes to own their reservation lands, and the right to self-determination enjoyed by all American citizens.

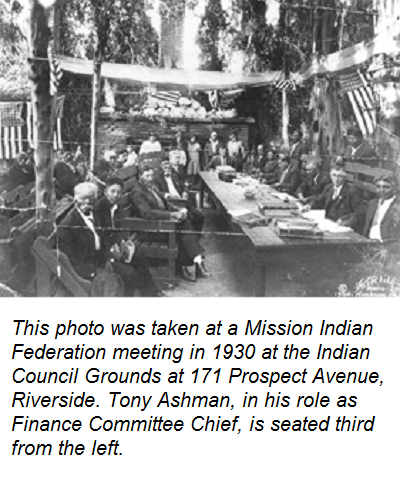

Jonathan Tibbet hosted semi-annual conventions at his home, and reservation Captains, members, and the public were given separate days to report to the Executive Council about their news and grievances. These meetings insured that reservation leaders and members met on a regular basis. Members received a button with the insignia of the MIF. The organization also published a magazine, The Indian, which was introduced in April 1921 and published monthly for the first few years and then sporadically during the existence of the organization. It educated MIF members about Indian affairs at the federal, state, and local levels. The magazine also circulated news from the reservations.

Jonathan Tibbet hosted semi-annual conventions at his home, and reservation Captains, members, and the public were given separate days to report to the Executive Council about their news and grievances. These meetings insured that reservation leaders and members met on a regular basis. Members received a button with the insignia of the MIF. The organization also published a magazine, The Indian, which was introduced in April 1921 and published monthly for the first few years and then sporadically during the existence of the organization. It educated MIF members about Indian affairs at the federal, state, and local levels. The magazine also circulated news from the reservations.